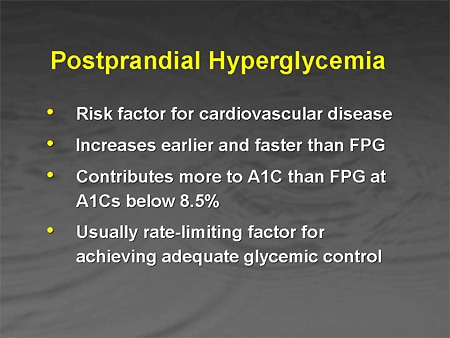

POSTPRANDIAL (after meals) hyperglycemia is one of the earliest abnormalities of glucose homeostasis associated with type 2 diabetes and is markedly exaggerated in diabetic patients with fasting hyperglycemia. And research conducted with human patients, mice, and pancreas beta cell cultures all point to a single threshold at which elevated blood sugars cause permanent damage to your body: 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/l) after meals.

Better control of postprandial blood glucose levels contributes more to improvement in HbA1c levels than fasting glycemic control. And since HbA1c is the gold standard for determining glycemic control among people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, all diabetics struggle to control the blood sugar round-the-clock.

However, a new research study from The Netherlands suggests that diabetics face a Sisyphean task ‒ postprandial hyperglycemia is highly prevalent throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients, including even those patients with HbA1c well below 7.0%.

Although postprandial hyperglycemia is recognized as an important target in type 2 diabetes treatment, information on the prevalence of postprandial hyperglycemia throughout the day is limited. The researchers therefore assessed the prevalence of hyperglycemia throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients and healthy controls under standardized dietary, but otherwise free-living conditions.

The researchers recruited 60 male type 2 diabetes patients (HbA1c 7.5 ± 0.1%) and 24 age- and BMI-matched normal glucose tolerant controls to participate in a comparative study of daily glycemic control. During a 3-day experimental period, blood glucose concentrations throughout the day were assessed by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

The researchers discovered that type 2 diabetes patients experienced hyperglycemia (glucose concentrations > 180 mg/dl [10 mmol/l]) 38 ± 4% of the day. Even diabetes patients with an HbA1c level below 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) experienced hyperglycemia for as much as 24 ± 5% throughout the day. Hyperglycemia was negligible in the control group (3 ± 1%).

After evaluating the data, the researchers concluded that hyperglycemia is highly prevalent throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients, including even those patients with HbA1c well below 7.0%. More importantly, “standard medical care with prescription of oral blood glucose lowering medication does not provide ample protection against postprandial hyperglycemia,” the authors wrote.

The aim of every diabetic is to keep postprandial blood sugar levels in line with the recommendations of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, an organization of specialists who treat diabetes, that blood sugar should not be allowed to rise above 140 mg/dl two hours after a meal. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) has also adopted the 140 mg/dl post-meal blood sugar target.

Since, as Dutch study shows, a majority of patients with diabetes fail to achieve their glycemic goals, it means elevated postprandial glucose (PPG) concentrations contribute to suboptimal glycemic control.

What is the contribution of PPG to the long-term complications of diabetes? Many studies have demonstrated a positive association between diabetic complications and hyperglycemia. “Complications" is a euphemism for some very ugly outcomes that include blindness, amputation, kidney failure and death. Considering the interrelationships among glycemic measures, this is not surprising.

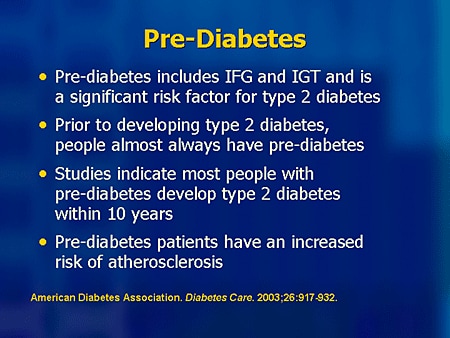

A team of Italian researchers led by A Gastardelli started examining beta cell response to glucose in people with normal blood sugars discovered that a small amount of beta cell dysfunction began to be detectable in people whose blood sugar rose only slightly over 100 mg/dl on a 2-hour glucose tolerance test. The beta cells are the cells in the pancreas that produce the insulin your body uses to control your blood sugar.

Analyzing their data further, they found that with every small increase in the 2-hour glucose tolerance test result, there was a corresponding increase in how much beta cell failure was detectable. The higher a person's blood sugar rose within "normal" range, the more beta cells were failing.

In another study, University of Utah neurologists found that patients who were not known to be diabetic, but who registered 140/mg or higher on the 2-hour sample taken during a glucose tolerance test were much more likely to have a diabetic form of neuropathy than those who had lower blood sugars. Even more telling, the researchers found that the length of time a patient had experienced this nerve pain correlated with how high their blood sugar had risen over 140 mg/dl on the 2-hour glucose tolerance test reading.

It is important to note that this study also showed that only the glucose tolerance test results corresponded to the incidence of neuropathy in these patients, not their fasting blood sugar levels or their results on the HbA1c test. This is significant because most American doctors do not offer their patients glucose tolerance tests, only the fasting glucose and HbA1c tests that fail to diagnose these obviously damaging post-meal blood sugars.

Given facts such as these, what does a diabetic do? Jenny Ruhlsuggests that if your blood sugar has been very high for a while, you can bring down the levels by proceeding in stages, setting your blood sugar targets progressively lower, a step at a time. But don't stay at higher than normal levels for any longer than is absolutely necessary. Once your body does adapt, you will probably feel much better and much more energetic than before.

Ruhl recommends patience while your body becomes accustomed to new, healthy, blood sugar levels, cautioning not to respond to feeling as if you were having a hypo by eating carbs to push up your blood sugar as long as your blood sugar tests at 80 mg/dl (4.4 mmol/l) or above. Give your body a chance to adapt and eventually you will feel completely normal when you have a normal blood sugar and may feel surprisingly toxic when your blood sugar reaches the dangerously high levels that you used to feel normal at, she says.

The 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L) blood sugar target is a good start, but many of us find we feel better and get even more normal health if we shoot for truly normal blood sugars and keep our blood sugar under 120 mg/dl (6.7 mmol/L) at all times. If you can do it, go for it. Now that we know that heart attack risk rises significantly at HbA1c in the mid 5% range, getting to true normal is that much more important, Ruhl concludes.

Better control of postprandial blood glucose levels contributes more to improvement in HbA1c levels than fasting glycemic control. And since HbA1c is the gold standard for determining glycemic control among people with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, all diabetics struggle to control the blood sugar round-the-clock.

However, a new research study from The Netherlands suggests that diabetics face a Sisyphean task ‒ postprandial hyperglycemia is highly prevalent throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients, including even those patients with HbA1c well below 7.0%.

Although postprandial hyperglycemia is recognized as an important target in type 2 diabetes treatment, information on the prevalence of postprandial hyperglycemia throughout the day is limited. The researchers therefore assessed the prevalence of hyperglycemia throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients and healthy controls under standardized dietary, but otherwise free-living conditions.

The researchers recruited 60 male type 2 diabetes patients (HbA1c 7.5 ± 0.1%) and 24 age- and BMI-matched normal glucose tolerant controls to participate in a comparative study of daily glycemic control. During a 3-day experimental period, blood glucose concentrations throughout the day were assessed by continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

The researchers discovered that type 2 diabetes patients experienced hyperglycemia (glucose concentrations > 180 mg/dl [10 mmol/l]) 38 ± 4% of the day. Even diabetes patients with an HbA1c level below 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) experienced hyperglycemia for as much as 24 ± 5% throughout the day. Hyperglycemia was negligible in the control group (3 ± 1%).

After evaluating the data, the researchers concluded that hyperglycemia is highly prevalent throughout the day in type 2 diabetes patients, including even those patients with HbA1c well below 7.0%. More importantly, “standard medical care with prescription of oral blood glucose lowering medication does not provide ample protection against postprandial hyperglycemia,” the authors wrote.

The aim of every diabetic is to keep postprandial blood sugar levels in line with the recommendations of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, an organization of specialists who treat diabetes, that blood sugar should not be allowed to rise above 140 mg/dl two hours after a meal. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) has also adopted the 140 mg/dl post-meal blood sugar target.

Since, as Dutch study shows, a majority of patients with diabetes fail to achieve their glycemic goals, it means elevated postprandial glucose (PPG) concentrations contribute to suboptimal glycemic control.

What is the contribution of PPG to the long-term complications of diabetes? Many studies have demonstrated a positive association between diabetic complications and hyperglycemia. “Complications" is a euphemism for some very ugly outcomes that include blindness, amputation, kidney failure and death. Considering the interrelationships among glycemic measures, this is not surprising.

A team of Italian researchers led by A Gastardelli started examining beta cell response to glucose in people with normal blood sugars discovered that a small amount of beta cell dysfunction began to be detectable in people whose blood sugar rose only slightly over 100 mg/dl on a 2-hour glucose tolerance test. The beta cells are the cells in the pancreas that produce the insulin your body uses to control your blood sugar.

Analyzing their data further, they found that with every small increase in the 2-hour glucose tolerance test result, there was a corresponding increase in how much beta cell failure was detectable. The higher a person's blood sugar rose within "normal" range, the more beta cells were failing.

In another study, University of Utah neurologists found that patients who were not known to be diabetic, but who registered 140/mg or higher on the 2-hour sample taken during a glucose tolerance test were much more likely to have a diabetic form of neuropathy than those who had lower blood sugars. Even more telling, the researchers found that the length of time a patient had experienced this nerve pain correlated with how high their blood sugar had risen over 140 mg/dl on the 2-hour glucose tolerance test reading.

It is important to note that this study also showed that only the glucose tolerance test results corresponded to the incidence of neuropathy in these patients, not their fasting blood sugar levels or their results on the HbA1c test. This is significant because most American doctors do not offer their patients glucose tolerance tests, only the fasting glucose and HbA1c tests that fail to diagnose these obviously damaging post-meal blood sugars.

Given facts such as these, what does a diabetic do? Jenny Ruhlsuggests that if your blood sugar has been very high for a while, you can bring down the levels by proceeding in stages, setting your blood sugar targets progressively lower, a step at a time. But don't stay at higher than normal levels for any longer than is absolutely necessary. Once your body does adapt, you will probably feel much better and much more energetic than before.

Ruhl recommends patience while your body becomes accustomed to new, healthy, blood sugar levels, cautioning not to respond to feeling as if you were having a hypo by eating carbs to push up your blood sugar as long as your blood sugar tests at 80 mg/dl (4.4 mmol/l) or above. Give your body a chance to adapt and eventually you will feel completely normal when you have a normal blood sugar and may feel surprisingly toxic when your blood sugar reaches the dangerously high levels that you used to feel normal at, she says.

The 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L) blood sugar target is a good start, but many of us find we feel better and get even more normal health if we shoot for truly normal blood sugars and keep our blood sugar under 120 mg/dl (6.7 mmol/L) at all times. If you can do it, go for it. Now that we know that heart attack risk rises significantly at HbA1c in the mid 5% range, getting to true normal is that much more important, Ruhl concludes.